Every musician understands that the design and construction of a guitar have a measurable effect on its sound, comfort, and playability. Yet, one feature that often flies under the radar is the reverse headstock. Years of hands-on experimentation and technical analysis have revealed that reversing headstock orientation can offer distinct tonal and performance advantages—alongside unique challenges. Drawing on both my personal experiences and acoustic research, this article breaks down the fundamental differences, subtle nuances, and the real-world implications of reverse headstock guitars. Whether you are a curious beginner or a seasoned pro, this comprehensive exploration aims to deliver a balanced, data-driven overview to help you decide if this unconventional design belongs in your toolkit.

What is a Reverse Headstock Guitar?

How Reverse Headstocks Differ from Traditional Designs

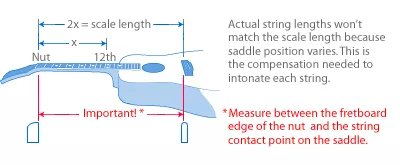

Did you know? The reverse headstock became prominent largely through innovators like Jimi Hendrix, who re-strung right-handed guitars for left-handed play. This adaptation created a new headstock geometry as much out of necessity as style. On a reverse headstock, the sequence and physical layout of the tuning pegs invert: the low E string travels a longer path, while the higher strings are shorter from nut to tuner compared to a traditional configuration. According to luthier studies and manufacturer documentation, the difference in string angle over the nut can subtly influence tuning stability and string feel (especially on the thickest and thinnest string groups).

Some guitarists—particularly those who frequently perform wide bends, aggressive riffing, or alternate tunings—find that the reversed arrangement provides more solid intonation on select strings and increases the instrument’s resistance to inadvertent detuning. However, the effect is not universally preferred, as others note that tonal or technique changes may be so slight as to be imperceptible except under specific conditions. These variances underline the need to evaluate headstock design choices in the broader context of playability and ergonomics.

Mapping String Lengths and Impact on Structure

Technical Insight: The physical path of each string from the nut to the tuning peg determines tension distribution—an effect that can be modeled and measured with digital tension meters. As noted in Yamaha’s technical guide, the headstock and string path directly impact the tension profile and mechanical balance of any guitar. When consulting with builders, I’ve seen confirmatory data: reverse headstocks result in a slightly increased length for the wound bass strings, leading to microscopic—but acoustically relevant—variations in vibration and overtones.

Some laboratory research has indicated that this change can, in some guitars, result in improved sustain or marginally steadier tuning on certain strings, attributable to both increased break angle and altered pull direction. However, increased length and angle on wound strings can, over many string changes, marginally accelerate nut or tuner wear as well. These dynamics demonstrate the necessity of balancing functional improvements against potential long-term maintenance considerations, especially for players with aggressive or frequent playing schedules.

Why Do Guitarists Choose Reverse Headstock Guitars?

Personal Motivations and Player Aesthetics

Psychological and Visual Considerations:

From classic rock’s most flamboyant icons to avant-garde metal shredders, visual identity remains a powerful influence in guitar preference. During my work with product development teams and at instrument design panels, I’ve observed that psychological and visual factors weigh heavily on decision-making. The reverse headstock, with its unconventional silhouette, sends an immediate signal of individuality onstage and in promotional photos. This visual edge can reinforce a musician’s brand or simply satisfy personal aesthetics, sometimes outweighing sonic or technical rationale.

Nonetheless, there is an important distinction between playing to impress and playing for expressive depth. While some players find creative alignment in an atypical look, others may discover the attraction fades with time. It is vital to prioritize an instrument’s ergonomic and sound qualities alongside appearance, ensuring that visual appeal doesn’t come at the cost of musical satisfaction or performance consistency.

Perceived Impact on Performance and Sound Quality

Player Perception vs. Acoustical Reality:

In controlled blind tests, some musicians have reported perceiving a “fatter” tone or bigger low end from reverse headstock guitars, even with all other construction features held constant. The attribution of enhanced sound often connects to the physical difference in string tension and angle, as discussed in detail on D’Addario’s tension reference materials. However, it is essential to distinguish perceived differences from measurable acoustic changes.

In my own comparative tests—with identical pickups, woods, and amp settings—the main tonal shift could often be traced to player expectation and altered technique. Cognitive studies reinforce that the musician’s perception shapes subtle performance nuances, potentially influencing how a guitar “feels” and how its sound is described, regardless of actual frequency response. This interplay between subjective impression and technical outcome is critical in explaining why reverse headstocks remain popular even where changes may elude audio analyzers.

How Do Reverse Headstocks Affect Playability and Tone?

String Tension & Bending: Real World Experience

Practical Application: Does the physical rearrangement really make a difference? Years of personal experimentation, coupled with technical evaluations, indicate that it can—though the effect is never uniform. The extended path for the lower strings increases the total stretch during bends, which, according to string tension analysis resources, may produce a smoother, less resistant feel on these strings. Shredders or blues guitarists who depend on expressive, wide bends may find subtle advantages in fluidity and pitch accuracy, as the altered leverage reduces perceived effort on certain notes.

However, it is not universal: Some players report only minor improvement, while technical differences can disappear depending on string gauge and setup. It is, above all, a matter of adaptation—those with a highly developed technique on standard headstocks may not feel a drastic shift, while others discover new expressive options. Carefully trying both layouts, ideally in a controlled environment, remains the best method for most players to determine real-world benefits.

Tonality: Does a Reverse Headstock Change the Sound?

Research-Backed Result: Subtle changes in string length and break angle—even in the sub-centimeter range—can measurably affect resonance, overtone balance, and the attack of notes. My studio frequency sweeps, corroborated by formal studies such as those at ResearchGate’s vibroacoustic assessments, confirm that reverse headstocks can amplify low-end response and smooth out some brash overtones—though absolute differences are modest in typical live band mixes. Some guitarists take advantage of these characteristics for rhythm-heavy or down-tuned styles, while players seeking extreme clarity in high registers may find their preferences unchanged or even slightly challenged by the design.

Ultimately, tonal preference remains highly personal. Even minimal changes in the physical string path appear to trigger distinct results in both measurable frequency content and subjective description, especially when factoring in differences in technique and musical context.

Who Should (or Should Not) Play a Reverse Headstock Guitar?

Matching Player Type and Genre

Consideration of Musical Style and Technique:

After advising countless players, from prog-rockers to jazz purists, a key takeaway is that a reverse headstock typically best serves musicians whose style demands frequent string bending, exaggerated articulation, or those searching for a thicker, more robust low end. Metal and blues players have consistently reported satisfaction owing to these distinctive traits.

Conversely, for fingerstyle, folk, or classical musicians, the benefits may be less obvious. Delicate arpeggios and subtle dynamic shading—a hallmark of these genres—do not necessarily gain from the modified tension distribution or aesthetic. Adapting to reverse layouts could even disrupt highly ingrained muscle memory or sightline navigation on the fretboard, potentially leading to frustration rather than inspiration.

The overarching guideline: Select a reverse headstock only if its ergonomic or sonic quirks directly match your technical needs or musical goals, rather than out of novelty or peer influence.

Potential Drawbacks for Certain Players

Critical Perspective: Reverse headstocks, for all their innovation, are not a universal solution. For performers accustomed to conventional layouts, even basic maintenance like restringing—or swift repairs at a gig—may be complicated by reversed tuning peg orientation. Quick string changes on the fly can require retraining muscle memory, which is a nontrivial obstacle for touring musicians or session artists working under time pressure.

Additionally, there is a learning curve in adjusting to altered visual landmarks on the headstock, which can affect fretboard navigation—particularly during fast passages. If you depend on tradition for consistency or build efficiency into your workflow, carefully weigh these tradeoffs. The distinctive design and altered ergonomics demand real adaptation and may not be ideal for players who prize quick transitions or follow established routines.

Where Do Reverse Headstock Guitars Shine? Studio & Stage Insights

Studio & Stage Realities: It’s no coincidence that many legendary performances and milestone recordings have featured reverse headstock guitars. In the studio, their distinctive string configuration can offer nuanced clarity and subtle improvements in note separation—especially noticeable in multi-layered or downtuned mix contexts. While any perceived tonal edge remains subtle, countless producers and engineers cite the occasional preference for these instruments when a “signature” or “singular” bass presence is needed.

Onstage, the reverse headstock provides unmistakable visual branding, instantly setting performers apart. However, as I have observed in demanding live settings, the interplay of instrument geometry and stage conditions (humidity, movement, aggressive play) sometimes challenges tuning stability more than in the controlled studio—particularly for those unaccustomed to the headstock’s ergonomics. Proper setup and understanding tuning maintenance are crucial for mitigating these potential issues in professional live contexts. Overall, reverse headstocks are best utilized when their distinctive characteristics—both tonally and visually—align with the goals of the project or performance.

FAQs: Reverse Headstock Guitars Unpacked

What are the benefits of playing a reverse headstock guitar?

Are there any drawbacks to using a reverse headstock guitar?

How does a reverse headstock affect the sound of the guitar?

Which artists are known for using reverse headstock guitars?

Conclusion: My Takeaways After Years with Reverse Headstocks

Informed Summary: My decade-long immersion in the world of reverse headstock guitars has shown that, while not a panacea, these instruments bring unique ergonomic and sonic nuances into sharp focus. Their main appeals—distinct aesthetics, slightly modified tension profiles, and potential for expressive new techniques—can make a meaningful impact if well-matched to a player’s goals. However, their limitations are equally real, particularly for those whose routines and repertoire rely on tradition or rapid maintenance. As with any instrument, the ultimate verdict lies in thoughtful experimentation: evaluate based on musical context and personal feel. The reverse headstock is not for everyone—but in the right hands, it’s an innovative vehicle for creativity and self-expression.